Before we dive into a detailed discussion, we need to first understand what audio is. First of all, sound is a wave, and the decisive factors are frequency and amplitude, where frequency determines the pitch of the sound, and amplitude determines the loudness. The human ear can generally hear sounds in the range of 20Hz to 20kHz.

Frequency

This is why we typically use audio sampled at 44.1kHz. If your sampling rate is less than or equal to twice the frequency, it cannot accurately represent the current sine wave. If you want to effectively convert music from an analog signal to a digital signal, you need a sampling rate greater than 40kHz. The general industrial standard is to reserve some space at 2.2 times the frequency, which is 44kHz.

HIFI companies like Sony choose 44.1kHz because it is above 40kHz and compatible with NTSC and PAL. Other rates like 48kHz, 96kHz, and 192kHz are also acceptable, but if you are not a professional, you generally cannot hear the difference. At the same time, the issue with high sampling rates is that the files will take up more space.

PCM

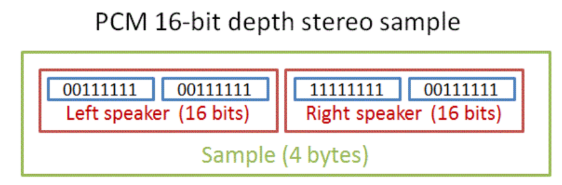

Pulse Coded Modulation is a common audio storage format. The audio devices we use generally play this type of audio directly. For example, the PCM data generated after decoding an AAC-encoded music file will be sent to the audio device's driver for playback. Each set of data stores one sample for each channel, and a sample can be a 16-bit integer or a 32-bit floating-point number, etc.

Fourier Transform

So how do we obtain the frequency of the original audio from a bunch of samples? For analog signals, we can use the Fourier Transform to convert a time-based function into a frequency-based function. In other words, you can apply the Fourier Transform to music to obtain all the frequencies and their intensities.

In simple terms, the Fourier Transform decomposes the audio wave at a specific moment into multiple standard waves with different amplitudes and frequencies.

However, our problem is that we only have digital signals, not analog signals. Fortunately, there is also the Discrete Fourier Transform.

The Discrete Fourier Transform can only be applied to a single channel. If you have spatial audio, you will need to convert it into a single-channel audio.

The formula for the Discrete Fourier Transform is as follows:

Where:

- N represents the size of the window, indicating how many samples are exposed in the current window.

- X(n) represents the frequency group of the nth bucket.

- x(k) represents the kth sample of the audio signal.

For example, when processing a window of 4096 samples, this formula needs to be calculated 4096 times. Where:

- When n=0, calculate the frequency group of the 0th bucket.

- When n=1, calculate the frequency group of the 1st bucket.

- ...

Note that the result calculated here is a frequency group rather than a frequency, because the result given by a DFT is a discrete spectrum. A frequency group is the smallest unit that DFT can calculate. We divide it into 4096 buckets, each responsible for about 10.7Hz of frequency range. For example, the frequency group in the first bucket is 0 to 5.38Hz (the first bucket is special), the second is 5.38 to 16.15Hz, which means that the current DFT cannot distinguish frequencies within a frequency group that differ by less than 10.77Hz, leading to a decrease in frequency resolution. If the frequencies of two notes fall within this same range, we cannot distinguish between them.

We can improve audio resolution by increasing the window size, but this will also increase computational overhead.

However, there is another pitfall when generating spectrograms using the Discrete Fourier Transform. If our sampling rate is 44.1kHz, frequencies above half of 44.1kHz cannot be accurately represented. When our frequency is , the result of the transformation is the same as (where x is the current frequency, and S is the sampling rate). Therefore, when performing the transformation, we only need to focus on half of the results, which is the spectrum from 0 to 22.05kHz.

Window Function

Since DFT requires us to segment the audio, if we want to analyze the spectrum over a very short time period, we need a window function to segment the audio samples.

Audio segmentation can lead to spectrum leakage. Due to the use of window functions, the energy of the true frequency can leak into other frequencies. For example, if your sampling rate is and the window size is , then if your frequency is not an integer multiple of , spectrum leakage will occur. You can reduce the impact of spectrum leakage by choosing a more appropriate window function, but you cannot completely avoid it.

FFT

The time complexity of directly performing the Discrete Fourier Transform is . We can speed up this process using a divide-and-conquer approach, where the time complexity of the Fast Fourier Transform is only . However, this requires the input length to be a power of two. If the original data length is not a power of two, we can adjust the length by padding with zeros.

Music Recognition

Spectrum Filtering

Since music recognition needs to tolerate noise, we need to filter the input audio to extract the loudest audio. However, we cannot directly determine the top X frequencies for each time segment because the human ear is less sensitive to low and high-frequency sounds. Therefore, many pieces of music undergo preprocessing to enhance low frequencies before release. If this is done, it can make two similar drum beats appear very similar in the spectrogram.

A better solution is to perform spectrum segmentation, dividing the entire frequency range into low, mid, and high frequencies, and selecting the strongest peaks from each band.

After performing spectrum filtering, we extract the strong feature points from the spectrogram, recording the song ID, occurrence time, frequency, and other information as the audio fingerprint of the song. By extracting several such audio fingerprints per second, we can match music in a database.